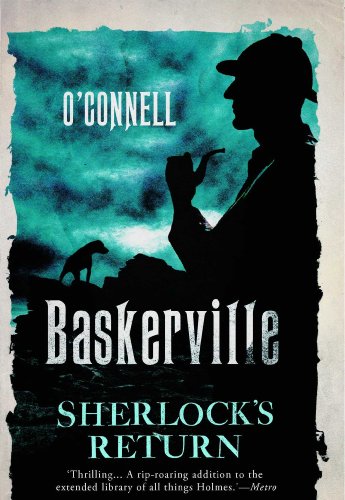

Items related to Baskerville: The Mysterious Tale of Sherlock's...

Dartmoor, 1900. Two friends are roaming the moors: Arthur Conan Doyle – the most famous novelist of his age – who has recently killed off his most popular creation, Sherlock Holmes; and Bertram Fletcher Robinson – Holmes aficionado and editor of the Daily Express.

They are researching a detective novel, a collaboration starring a new hero, set in the eerie stillness of ancient West Country moorland, and featuring a monstrous dog. They already have a title...

London, 1902. The Hound of the Baskervilles is published, featuring Sherlock Holmes back from the dead. Conan Doyle and Fletcher Robinson have not spoken for two years and the book is credited to just one author. It will become one of the most famous stories ever written. But who really wrote it? And what really happened on those moors, to drive the two friends apart?

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

Chapter 1

It is often hard to recall the exact circumstances of a meeting. But I can say for certain that I first met Dr Arthur Conan Doyle on the morning of July 11th, 1900. We were waiting to sail from Cape Town back to Southampton on the SS Briton, the most graceful of the Union mail steamers.

Like every other available vessel, the Briton had been requisitioned as a troop transport. It had done well in the early days of the second South African war, rushing out some 1,500 soldiers in under 15 days. Now she was bringing them back; some of them, at any rate, for our fight against the Boer was far from over.

As I leaned over the deck rail, straining for a better view of the gaunt Tommies waiting to board, a voice close behind startled me so that I almost lost my balance.

‘Of course,’ it said, ‘a good many of them will be afflicted by enteric fever.’

It was a deep, confident voice lent charm by a slight Scottish accent. I turned and was confronted by its owner, a man I recognised immediately from engravings and photographs as the creator of Sherlock Holmes; though as I said, I had not met him before.

He, however, believed differently. ‘We’ve been introduced,’ he said. ‘You are Bertram Fletcher Robinson, journalist and sports writer.’

I agreed that I was. But I also admitted, as I felt I must, that I had no memory of our meeting.

Doyle appeared unconcerned. ‘It was at the Reform Club. You are a Reformer, aren’t you?’

‘I am.’

‘Well then,’ he said, as if that concluded the matter.

Like me, Doyle is a tall man, his build stout and athletic. But he had lost weight in Bloemfontein, where he was working as voluntary supervisor at Langman’s field hospital; so much that his double-breasted linen suit billowed out in a manner it was hard not to find comical.

I had noticed when we shook hands that his skin was clammy. Considering him now, more attentively, it was obvious he was unwell. Every so often a ripple passed across his pale face as if from some palsy. The weather was not yet hot – on the contrary, there was a pleasantly light morning breeze – but fat beads of perspiration glistened on his forehead.

Doyle saw my concern. ‘Please don’t worry,’ he said. ‘I was inoculated with the serum on the way out. Whatever this is, it’s nothing serious.’

‘Can you be sure?’

He smiled weakly. ‘Self-diagnosis is a doctor’s greatest pleasure.’

We stood there for what might have been ten minutes – not talking, just gazing at what we were shortly to leave behind: Cape Town itself, spread out along the margin of the bay; Table Mountain, whose broad, flattened summit I still longed to visit; and the whole noisy scrum of wharf life, so intoxicating when first you encountered it: Malays and Kaffirs in various states of undress, all wanting to carry your luggage to the custom-house or get you a wagon or sell you fruit – great dewy heaps of purple and white grapes, nectarines, figs, melons, apricots, all wonderfully cheap.

It was Doyle who broke the silence. ‘Such a charming place,’ he said. ‘A fine country. Anyone with any energy could make a fortune here in no time.’

‘I’ve plenty of energy,’ I said, ‘but not for mining or entrepreneurialism.’

‘No? For what, then?’

‘I’m to be Managing Editor of the Daily Express. It’s why I’m returning to London.’

At this Doyle insisted on shaking my hand again. ‘My dear fellow, congratulations! They must be pleased with your work out here. Now I remember, there was an Express at the hospital and I read one of your dispatches. What was it called – “Cape Town for Empire”? Do I have it right?’

‘That was my first,’ I pointed out, not without pride.

‘Was it? Well, well. It was very good. Very thoughtful. I’m writing something myself, as it happens. A history of the conflict. I should have it finished soon.’

He stopped suddenly, gripped the deck rail and shuddered, as if a wave of nausea had overtaken him.

I rushed forward and made to grasp his arm. ‘Dr Doyle?’

He put up a hand. ‘Please. It will pass. We must talk another time, over dinner. I won’t want food tonight, but this thing comes and goes.’

‘Perhaps tomorrow evening?’

‘Yes, yes. Come to the first-class saloon for seven o’clock.’

With this Doyle turned and, using the rail for support, edged cautiously along the deck in the direction of his cabin.

Doyle had a cabin to himself on the main deck. My quarters were less salubrious, though still not too badly appointed: those of us with War Office press passes were billeted in what would have been first class.

About a hundred soldiers slept on the lower deck in hammocks strung up in rows. I went there only once, in a spirit of journalistic enquiry. I found the conditions cramped and stifling, rendered more unpleasant still by the want of convenience for washing.

Once the anchor was drawn up we soon lost sight of Cape Town and the Cape of Good Hope. Though the sky remained clear and blue, sailing conditions worsened. A heavy beam swell rolled us around and I came close to adding my own weave to the fetid carpet I had noticed on the deck below.

Evidently Doyle felt wretched as well. He postponed our dinner – first one night, then another.

The monotony of shipboard life gets to everyone and I confess I grew jittery and impatient. Weary, too. Too weary to take pleasure in sights I had relished on the way out, like the shoals of flying fish and even the other passing steamers, identification of which had once been the goal of much clamorous and excited sharing of field glasses.

My attempts to organise races and other athletic activities came mostly to nothing. One afternoon I persuaded several soldiers to join me in a game of deck-quoit. When their enthusiasm waned, too quickly for my liking, I passed the time reading and playing chess with a nonconformist missionary whose foul breath I had to turn my head to evade.

I also wrote at length to Gladys, my fiancée, knowing I could post the letter in Las Palmas when we stopped to take on coal.

I told her of my excitement at meeting Doyle. She would understand, I knew; for like me she had read with awe every Sherlock Holmes story. She shared my frustration at Doyle’s decision seven years before to kill off the great detective in ‘The Final Problem’.

How can I do justice to Gladys?

Perhaps I can’t.

Let me just say that while I was away I carried in my head not merely her image – the golden ringletted hair; the light-grey eyes which seem to communicate the finest gradations of thought; the roundness and smoothness of her cheeks – but a sense-memory of her exuberant vitality. It was palpable, physical, like stray hairs left behind on a brush, or the floral smell of her neck as I stooped to kiss her.

Her letters had sustained me on the front line. I loved them for their combination of domestic detail and political analysis; though I confess their naïve radicalism made me smile. Gladys styled herself a ‘New Woman’, enlightened and alert.

Before I left England she had tried to persuade me to read a novel, ‘The Story of an African Farm’, which she assured me would illustrate ‘the full complexity of the African predicament’.

I am afraid I put it to one side.

Her letters were full of questions. How was it that a raggle-taggle band of amateur farmers could be a match for the British army? Pax Britannica was all very well, but did we really have a divine right to civilise the world? What if the world chose to resist our interventions?

Still, her most recent letter, dated May 19th, had been full of the celebrations that followed the relief of Mafeking – an event of which everyone has surely heard and which I was fortunate enough to witness at close hand.

In London, so Gladys told me, a large picture of Colonel Baden-Powell had been fixed over the Mansion House balcony. Appearing to huge cheers, the Lord Mayor told the crowd: ‘British pluck and valour, when used in a right cause, must triumph.’

Gladys was among the crowd that night. Her friends made sure of it and her letter duly reports it: proof, I think, that for all her convictions she was not immune to pomp.

Four days into the voyage I received word from Doyle that he was much improved. Would I join him for dinner that evening?

The first-class saloon retained its pre-war air of elegant tranquillity. Doyle arrived ten minutes late, all abustle, apologising for his poor timekeeping. He looked better, sprightlier. His eyes twinkled and his cheeks were ruddy.

‘I was distracted by a cockroach in my cabin,’ he explained, taking a seat opposite me. ‘At first I wasn’t sure. I knew it was some species of orthoptera. So I got down on my hands and knees’ – he mimed this action – ‘and examined it more closely.’

‘What did you discover?’

‘That its antennae were long and setaceous, while its abdomen had two jointed appendages at the tip. Definitely a cockroach!’ Doyle laughed heartily. It was a wonderful sound – rich and warm.

We smoked for some while, then in the dining room had a good meal of beef and potatoes; also the bottle of St Emilion I had won in Ladysmith in a card game and had been keeping for just such an occasion.

Conversation was loose and amiable. It ranged across rugby football – my passion and the subject of a recent book of mine; the difficulty of digging trenches in the dry, rocky soil of the veldt; the rumours that our troops at Mafeking had survived by eating locusts and oat husks. ‘If they’re true then they shame us all,’ said Doyle, and I could only agree.

He was used to boats. As a young man he had gone whaling in the Arctic, then a few years later to West Africa. He had done so to save money to start in practice as a doctor. ‘But’ – he held up a finger – ‘I nearly didn’t make it back.’

‘No?’

‘One afternoon I went swimming at Cape Coast Castle. The black folk jumped into the water freely enough, I didn’t see why I shouldn’t. It was only later, as I was drying myself on deck . . .’ He paused, smiling.

‘What?’ I asked. ‘What happened?’

‘I saw the triangular black fin of a shark rise to the surface!’

You were never sure of the truth of Doyle’s stories. That was part of their appeal.

The conditions in the hospital sounded awful. Rows of emaciated men. Flies everywhere – all over your food, forcing themselves into your mouth whenever you tried to eat or speak.

Langman’s had erected its tents on a cricket pitch near the centre of Bloemfontein. The pavilion became its main ward. At one end was a stage set for a performance of ‘HMS Pinafore’.

Typhoid struck when the Boers cut off the water supply, forcing use of the river and whatever stagnant water could be retrieved from local wells. The stage found itself pushed into service as a latrine – though as Doyle explained, few reached it in time: ‘The nurses were busy with their mops!’

There were no coffins. Men were lowered in their blankets into shallow graves at a rate of 60 a day.

It all begged the question: Why had Doyle decided to volunteer? He was a successful author, no longer in youth’s impetuous grip; no longer morally obliged to serve his country as he would have been even five years earlier. (He had sought a commission and been rejected as too old: ‘At 41! I ask you!’) Why, I asked him, had he risked his life and the happiness of his family in this fashion?

He thought for a moment. ‘If the health of the Empire is to be honoured, it’s a rifle one must grasp, not a wine glass.’

‘What about a pen?’

‘I grasp that too. But it isn’t always enough.’

There was something else, though; another factor in his desire to get away from England and follow an unfamiliar path – caring for his consumptive wife Louisa (or ‘Touie’, as he called her) had become burdensome.

‘I’ve lived for six years in a sick room,’ he said, ‘and I’m weary of it.’

He sounded sincere. But I wondered, then as now, about the extent of his involvement in his wife’s care and if his loyalty to her was as profound as he claimed. More than once he mentioned a ‘very good friend’ by the name of Miss Leckie. Each time, his face flushed and his voice developed a croak so that he had to clear his throat noisily.

It was via this conversational conduit that I was able, eventually, to raise the subject of Sherlock Holmes – one I had avoided as I suspected it was off-limits and did not wish to seem gauche.

Doyle made a reference to this Miss Leckie’s skills at plotting, implying that she herself had helped him with some of the stories.

‘She goes right to the nub of things,’ he said. ‘The way she traces the arc of a story, so that irrelevancies fall away. There’s something magical about it. Something alchemical, like a burning off of impurities.’

The croak came again. I spied my opening.

‘It would be strange,’ I began, ‘to sit here and not tell you how much I admire your work. “Rodney Stone”, for example . . .’

‘Rodney Stone’ was a novel about boxing which, as a sportsman, I had enjoyed; though no-one would count it among its author’s greatest successes.

Doyle looked pleased. His moustache twitched approvingly.

‘ “The Tragedy of the Korosko”,’ I went on. ‘It’s hard not to think of it, in our current situation. So many scenes imprint themselves on the memory.’

The reader will not need reminding that this novel, one of Doyle’s best, unfolds on a River Nile passenger steamer. A group of tourists is attacked and abducted by a band of Dervish warriors.

Doyle raised his hand, bidding this fusillade of praise cease. ‘You’re very kind,’ he said. ‘So kind that I hope what I’m about to ask you won’t strike you as strange. But I’m curious. Have you read my most recent novel, “A Duet”?’

I admitted I had not and his face fell. ‘Its publication coincided with my posting,’ I said. ‘I couldn’t find a copy before I left London.’

Doyle smiled in appreciation of a nice try. ‘It didn’t catch, that’s the truth of it. It was a personal book, and quite effortful – to write, I mean. It’s about a marriage. Are you married?’

‘I hope to be. I’m engaged.’

‘Aha!’ He clapped his hands, pleased to lighten the mood. ‘Who is she?’

‘Gladys Hill Morris. Perhaps you know her father, Philip Richard Morris?’

‘Is he a painter?’

‘He’s known for his maritime scenes.’

‘I recognise the name. I don’t know his work.’

A silence settled over our table. Doyle drained his glass and looked about him at the other diners. Was he going to call an end to the evening? I couldn’t permit that, not yet.

The question burst forth, like a suppressed sneeze: ‘And what of Holmes?’

Doyle looked startled. ‘Holmes,’ he said, as if struggling to recall a figure from the distant past.

‘Do you miss him?’

It was an idiotic question. Looking back, I can’t believe I asked it.

And yet it was answered.

‘I do,’ said Doyle, gently. ‘It’s a curious business, the relationship between a...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherAtria Books/Marble Arch Press

- Publication date2013

- ISBN 10 1476730237

- ISBN 13 9781476730233

- BindingPaperback

- Number of pages192

- Rating

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Baskerville : The Mysterious Tale of Sherlock's Return

Book Description Condition: Good. Original. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Seller Inventory # 1391043-6

Baskerville: The Mysterious Tale of Sherlock's Return

Book Description Paperback. Condition: Good. No Jacket. Former library book; Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 0.36. Seller Inventory # G1476730237I3N10

Baskerville: The Mysterious Tale of Sherlock's Return

Book Description Paperback. Condition: Good. No Jacket. Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 0.36. Seller Inventory # G1476730237I3N00

Baskerville: The Mysterious Tale of Sherlock's Return

Book Description Paperback. Condition: Very Good. No Jacket. Former library book; May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 0.36. Seller Inventory # G1476730237I4N10

Baskerville: The Mysterious Tale of Sherlock's Return

Book Description Paperback. Condition: Very Good. Very Good. Gently used with NO markings in text; binding is tight. Pasadena's finest independent new and used bookstore. Seller Inventory # mon0000289257

Baskerville: The Mysterious Tale of Sherlock's Re

Book Description Paperback. Condition: Very Good. Original. Baskerville: The Mysterious Tale of Sherlock's Return. Seller Inventory # FORT437298

Baskerville: The Mysterious Tale of Sherlock's Re

Book Description Paperback. Condition: Very Good. Original. In our warehouse. Seller Inventory # JAM559246